The Iran Enablers: Tehran’s Network in America

Endowment for Middle East Truth

Endowment for Middle East Truth

The Iran Enablers: Tehran’s Network in America

Washington, D.C. August 26, 2024

Executive Summary

- Most lobbying for Iran’s Islamic republic stems from a loud, sympathetic minority within the United States’ Persian diaspora, non-interventionist American leftists, and businesses looking for access to Iran’s sizable market and oil reserves.

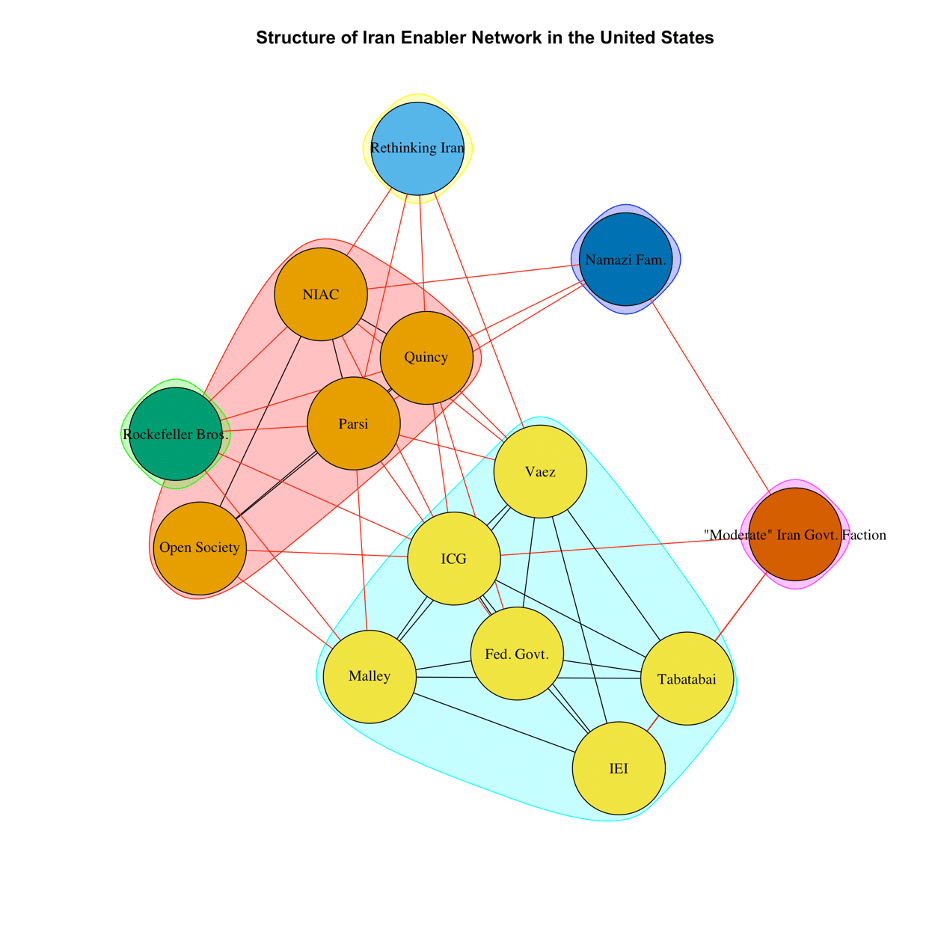

- America’s Iranian influence network has bureaucratic, ideological, and diaspora pillars. Each component has a different organization, but the network’s members may belong to more than one component.

- The National Iranian American Council (NIAC) represents the network’s diaspora component. Despite its purported goal of helping Iranian Americans organize as a community within the United States, most of NIAC’s work, including its “human” aspect, focuses on sanctions relief for the Iranian regime in the name of dialogue and helping ordinary people, such that Iranian students in the United States would benefit from NIAC’s proposals more than any other diaspora demographic group. Many people inside NIAC share an obsession with the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) and the lobbying efforts of the American Jewish community on behalf of its interests.

- NIAC has directly lobbied for the Iranian regime and promoted its favored policy positions. In 2007, NIAC sued reporter Hassan Daioleslam for defamation after he uncovered those activities. To bolster its viewpoints, NIAC has sought to gaslight, suppress, intimidate, and ignore most Iranian Americans, who are opponents of Tehran’s Islamic theocracy, along with its allies. It also has tried to characterize Iran’s radical Islamist regime as a government like any other. To allow it to engage in lobbying efforts, NIAC has created a political action committee (PAC) known as NIAC Action.

- The Quincy Institute stands for the network’s ideological component. Headed by fervent anti-interventionists, the Quincy Institute advocates for a recklessly unmitigated American withdrawal from most of the world in the name of dialogue so that a power vacuum exclusively favorable to the adversaries of the United States would ensue. Replicating the Quincy Institute’s preferred policies would repeat the 2021 Afghanistan debacle.

- Trita Parsi has founded and is involved with NIAC and the Quincy Institute. He was also one of the figures who gave intellectual backing to the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA, or Iran deal). His background and the work he performed for his adopted country, Sweden, at the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), and Congressman Robert Ney suggest that a non-negligible part of the pro-Iranian regime movement, including Parsi himself, either has left-wing and Third World ideals or looks to do business with Iran. Parsi’s regime connections mean that his work at the Quincy Institute entails a larger stage to hinder American interests, for it can help him coordinate multiple causes and simultaneously benefit most United States adversaries.

- Other people within the network who advocate for normalization with Iran and question the role of American sanctions are professors like Vali Nasr and Narges Bajoghli. Along with Trita Parsi and other professors, they toil to change mainstream American views on Iran.

- The International Crisis Group (ICG) and its most prominent members represent the pro-Iranian regime network’s bureaucratic component. Founded to end wars—even at the cost of appeasing destabilizing regimes—most of the ICG’s board of directors has belonged to the United Nations (UN) bureaucracy or the federal government’s or European Union’s (EU) staff.

- For Iran’s influence network, the ICG’s most prominent people have included Robert Malley, Special Envoy for Iran; Dina Esfandiary and Alireza Vaezzadeh (also known as Ali Vaez). They all partook in the Iran Experts Initiative (IEI), aimed at spreading the Iranian regime’s viewpoints in academia, according to leaked emails published by news website Semafor. Ariane Tabatabai, who works at the Department of Defense participated in this initiative as well. Except for Robert Malley, who has been on leave since June 2023, most IEI people in the federal government have held on to their jobs and have not suffered any disciplinary actions. Tabatabai even visited registered visits to the White House until April 2024. Robert Malley’s links to Secretary of State Anthony Blinken and Philip Gordon’s link to Vice President Kamala Harris are of the highest concern.

- Ali Vaez, a nuclear physicist, organic chemist, and Georgetown University international relations professor, is another one of the network’s intellectual heavyweights. He has featured prominently in his quest for the normalization of Iran’s regime. He has worked for NIAC and has headed the ICG’s Iran program. He was one of the JCPOA’s greatest promoters, alongside Vali Nasr, Narges Bajoghli, and Trita Parsi.

- The network’s most salient financing involves the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, the Open Society Foundations, the Ploughshares Fund, the Carnegie Corporation, the Herbert Luce Foundation, the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, and some of the Quincy Institute’s board members. In the case of the ICG, it also includes the EU, the UN, the World Bank, and the governments of Qatar, Japan, South Korea, and Canada, alongside some European governments like those of France, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Belgium, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

- A fact about the network that one must not overlook is that, among its chief representatives, the members who were born in Iran after the late 1970s or early 1980s and those who left Iran after those years shy away from sharing biographical information with the public, including their hometowns, their family backgrounds, and the schools and universities they attended before they left Iran. Their common denominator is that they came to the United States as students.

Introduction

Since it became an Islamic republic in its 1979 revolution, Iran has become the top Middle Eastern adversary of its erstwhile cherished American ally. Amidst the chants of “death to Israel, death to America” and the desperate screams of the American diplomatic corps in Tehran, the Iranian regime started a lengthy process of consolidation. In it, the ayatollahs heading the new regime seized every opportunity to destabilize the Middle East. After Saddam Hussein’s attack, they sought to weaken Iraq and pushed it to the brink of financial ruin.[1] When the Israelis were driving Yasser Arafat’s Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) out of Lebanon because of its terrorist acts, the Iranians helped galvanize that country’s Shiite faction in the middle of Lebanon’s civil war to form Hezbollah, which killed 241 US servicemen in 1983.[2]

After the 2011 Arab Spring, Iran opportunistically exploited the hopes of millions of Arabs for more prosperity and accountability. It propped up Bashar al-Assad’s rule in Syria and prolonged its civil war, with a fatal outcome. By supporting the Houthis, Iran squandered hopes for a peaceful transition of power in Yemen. It also created a regional threat, which would end up attacking an oil refinery inside America’s Saudi Arabian ally in 2019.[3] In 2011, Iran capitalized on the withdrawal of American troops from Iraq and pushed its former foe out of the American sphere of influence. More worryingly, Iran is menacing the very existence of Israel, the United States’ top Middle Eastern ally and the world’s sole Jewish state, 80 years after the Holocaust.

Through its gains in Iraq and Syria after 2011 and its alliance with the most important political actor in Lebanon, Iran attained a military objective that had eluded it for so long: a direct route from which to threaten, harass, and attack Israel. Ever since, Israel, which had withdrawn from Southern Lebanon under the wholesome wish for peace, stood aghast as increasingly sophisticated weaponry reached its borders under Iranian auspices. To achieve its raison d’être of destroying Israel, Iran left no single link untouched. For this reason, Israel has faced a seven-front war since October 7, 2023, simultaneously combatting Hamas, Hezbollah, Syria, Iraq, Palestinian militants in Judea and Samaria, the Houthis, and an Iran so unhinged to launch hundreds of ballistic missiles—that miraculously left only one victim—against Israeli civilian population centers. Nevertheless, this scenario, as bleak as it sounds, pales in comparison to Iran’s nuclear program. As this paper is published, Iran is just several weeks away from developing a nuclear bomb. If we take the regime’s fanaticism into account, the ayatollahs could attempt a nuclear attack against Israel, whose population has the horrors of the Holocaust fresh in the minds of its people, many of whom are survivors. In an ordinary conflict, such a juncture would at least imply sanctions and would never involve talks of normalization; however, in the case of the double standards applied to Israel, such talk is bewilderingly commonplace.

In 2009, with the idea of diminishing tension between the United States and Iran, the Obama administration sought to engage in dialogue until the Iranian regime repressed the Green Movement protests after a questionable presidential election. In 2010, it ramped up the pressure on the United Nations (UN) to levy sanctions on Iran because of its nuclear program.[4] However, the Obama administration resumed its pro-normalization course and, near the end of 2013, sketched the first contours of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA, or Iran deal), wherein sanctions relief would match Iranian consent to International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) visits.[5] By 2015, despite an acrimoniously fought vote in the Senate, the United States committed to the Iran deal’s tenets and joined the other four UN Security Council (UNSC) permanent members and Germany as one of its interested parties. Nonetheless, the Trump administration exited the Iran deal in 2018 because of repeated Iranian violations of the JCPOA’s terms.[6] The Trump administration also imposed new financially punitive measures against Tehran to weaken its nuclear program and even ordered the assassination of Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) General Qassem Soleimani in 2020. However, the Biden administration’s choice to (still fruitlessly) revive the Iran deal and shy away from sanctions enforcement has emboldened the regime—which was already savvy in evading sanctions through clandestine finance operations, including proxy companies, according to an article from the Wall Street Journal—and may have contributed to the attacks against Israel on October 7.[7]

Behind the talks of normalization with Iran, there is a network. The pro-Iran interest groups include a loud, sympathetic minority within the United States’ Persian diaspora, non-interventionist American leftists, and businesses looking for access to Iran’s sizable market and oil reserves. As disparate as these groups can be, they have proven able to foster a suitable environment for their interests and to come together through the network’s three pillars: diaspora, ideology, and bureaucracy. As legally entitled as they are to advocate for their views, the network’s members are not alone; backing them has been the Iranian regime. Hence, combatting the network constitutes a paramount national security concern.

This paper will describe the Iranian enabler infrastructure within the United States.

- It will first explain how the network’s diaspora organization, the National Iranian American Council (NIAC), repeatedly eschews the concerns of ordinary Iranian Americans whenever they do not serve to bolster the cause of relief for the Iranian government; deceptively sidelines the majority of Iranian Americans, hostile to the regime; and uncannily exhibits an obsession with benefitting Iranian students in the United States and with discussing lobbying by the American Jewish community.

- After that, the paper will pivot to the network’s ideological component and its representative: the Quincy Institute (Quincy). Within that section, the paper will point to Quincy’s ideas and global reach, alongside its potentially catastrophic proposals of dauntless, planned American decline.

- Before transiting to the network’s bureaucratic pillar, the paper will focus on Trita Parsi: the common denominator of Iran’s diaspora and ideological components and one of the Iran deal’s chief proponents in the early 2010s.

- Delving into Parsi’s background and actions will make this paper showcase the non-interventionist, Mossadegh, and Third World affiliations that many of the Iranian regime’s enablers share. It will also outline Parsi’s regime connections and what his move from NIAC to Quincy may mean.

- The other step the paper will take before heading to the network’s bureaucratic component is examining Iranian American professors Vali Nasr and Narges Bajoghli and their work to challenge the predominant American perspective on Iran.

- Concerning the network’s bureaucratic component, the paper will explore the anti-war International Crisis Group (ICG) alongside its primary funding and staffing by the European Union (EU), the UN, and the US federal government.

- In the American context, the paper will examine how prominent ICG employees connected to the US federal government or NIAC, including Ariane Tabatabai, Robert Malley, Dina Esfandiary, and Alireza Vaezzadeh (Ali Vaez), were implicated in the Tehran-supported Iran Experts Initiative (IEI), instrumental in helping negotiate the JCPOA.

- The paper will include the network’s most prominent actions and funders. It will also focus on how some of the network’s most renowned members, who often came to the United States as students, suspiciously shy away from sharing relevant biographical information with the public.

- To conclude, the paper will advocate for expeditious government inquiries and punitive and preventive sanctions with immediate effect.

Figure 1.

The National Iranian American Council (NIAC)

NIAC covers the Iran enabler network’s diaspora pillar and is an offshoot of an organization known as Iranians for International Cooperation (IIC). According to journalist Eli Lake, IIC’s founding by Trita Parsi—whom this paper will treat below—dates to 1997, when Iranians elected so-called reformist president Mohammed Khatami. According to IIC’s former website, its main objectives were to “safeguard Iran’s and Iranian interests” and to ensure “the removal of U.S. economic and political sanctions against Iran, and the commencement of an Iran-U.S. dialogue.”[8] Three events in 1989 would lead to the creation of IIC: the end of the Iran-Iraq War, the death of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and his replacement by Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and the election of President Akbar Rafsanjani, who was willing to do business with Western countries as long as they did not challenge the Islamic republic. Because of these changes, many personalities with personal connections to the Iranian regime opted for the business route to profit from their contacts.[9]

Along with such people were the Namazi family. The family’s patriarch, Mohammad Bagher Namazi (Baquer Namazi), had been governor of the province of Khuzestan before the Revolution and, after 1983, was an Iranian immigrant to the United States. Seeing the opportunities that Rafsanjani’s regime afforded, Baquer Namazi’s sons Siamak and Babak, and his niece Pari and her husband Bijan Khajehpour, returned to Iran during the 1990s. Pari Namazi and Bijah Khajehpour founded Atieh Bahar Consulting (AB) in 1993 to help Western companies settle in Iran and gain access to the government.[10] Babak and Siamak Namazi joined AB between 1994 and 1996 after working at a law firm and Iran’s Ministry of Housing and Urban Planning, respectively. By 1997, the year of Khatami’s election, companies like BP, Statoil, Shell, Toyota, BMW, Daimler, Chrysler, Honda, MTN, Nokia, Alcatel, and HSBC were among AB’s Iranian clients. Only American firms were missing because, after public outcry against Conoco’s 1995 agreement with the Iranian government to exploit an offshore gas field, the Clinton administration imposed sanctions and forbade American companies from engaging in business with Iran.[11] One year later, in 1996, Siamak Namazi met Trita Parsi.[12]

Although it is uncertain whether Siamak Namazi played any role in IIC’s establishment in 1997, he did work with Trita Parsi to establish NIAC as its successor. As Siamak Namazi himself made known in 1998, IIC was still ineffective in influencing the American government.[13] Therefore, Namazi and Parsi decided to change their modus operandi. In a 1999 conference in Cyprus, both lay the justification for a diaspora organization sympathetic to normalizing relations with Iran based on encouraging dialogue and understanding and catalyzing the formation of an Iranian American interest group in the mold of the American-Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), which they perceived as an example of the power and influence of Jewish Americans to shape future leaders and turn them into pro-Israel advocates.[14] NIAC has consistently referred to what it deems a Jewish lobby. Parsi and Namazi’s outlook for NIAC included leadership seminars for Iranian American youth, detailing the harmful effects of sanctions on ordinary Iranians, and working on a new approach to relations with Iran.[15] Although Parsi would later dispute basing NIAC on AIPAC, this remains NIAC’s blueprint.[16]

In 2002, NIAC supposedly appeared as an organic response of part of the Iranian American community to condemn the 9/11 attacks and, at the same time, comfortably express openness to a rapprochement between Iran and the United States in the name of dialogue. Despite harboring IIC’s positions, two structural changes finally awarded Parsi the influence he had sought. One of those changes was to increase the flow of money that NIAC would receive by eluding a lobby designation and seeking 501(c)(3) tax-deductible status. This fundamental change would allow NIAC to receive $200,000 from the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), which partnered with Baquer Namazi’s Iran-based Hamyaran Foundation. The other one was to shed the Iran representative label by focusing more on the human aspect, including the discrimination that Iranian Americans were facing.[17]

After Parsi established NIAC’s position in the American political landscape between 2002 and 2005, he became confident enough to focus on NIAC’s real goal: rescinding sanctions against Iran.[18] Although Parsi had published an Iranian offer to President George W. Bush in 2003 to strike a grand bargain, NIAC only promoted rapprochement aggressively starting in 2006, when Parsi started to offer meetings between interested Americans—including members of Congress—and Iranian UN Ambassador Mohammad Javad Zarif under the excuse that, were there not dialogue between Iran and the United States, war would ensue because of the more aggressive government of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.[19] He even directly worked with billionaire George Soros towards that goal.[20] Shortly after, in 2007, Iranian diaspora journalist Hassan Daioleslam (also known as Hassan Dai) revealed NIAC’s lobbying efforts.[21]

Because the law only allows non-profits to use up to 20% of their funds for lobbying activities and NIAC’s lobbying was undisclosed (it reported no lobbying activities), NIAC should have had to pay financial sanctions for false reports and lost tax-exempt status.[22] Nevertheless, since it was firmly ensconced in the American political system, NIAC only had to make internal documents public because it sued Daioleslam for defamation in 2008—it also sought to exclude him from the Persian-language programs of Voice of America (VOA) and alleged that he was part of the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran Marxist terrorist group.[23] During the lawsuits, the judge reprimanded Parsi for modifying 1999 documents stating that IIC was an “advocacy” rather than a “lobbying” group. NIAC also did not produce 5,500 emails related to employee Babak Talebi, misrepresented how its computer and record systems worked, delayed handing the lists of its members by two-and-a-half years, and, according to audit firm PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), deliberately modified or deleted 4,159 calendar entries.[24] In 2012, the judge ruled against Parsi and ordered him to pay Daioleslam’s attorney fees; in a 2015 appeal decision, Parsi did not succeed at reversing the spirit of the decision but had its compensation amount revised downward: $183,480.09.[25]

After the regime suppressed the Green Movement in 2009 and steamrolled Ahmadinejad’s reelection, Parsi and NIAC momentarily lost popularity. The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) imposed sanctions on Iran in 2010 because of the repression and the regime’s obstinate continuation of the Iranian nuclear program. Besides the lawsuit against Daioleslam, the Iranian government imprisoned Bijah Khajehpour, who later fled to Vienna with his wife, while Siamak Namazi escaped to the United Arab Emirates.[26] In 2013, with the election of Hassan Rouhani—Khajehpour’s former employer and closer to Rafsanjani than Ahmadinejad—and Mohammad Javad Zarif’s appointment as Minister of Foreign Affairs, the situation changed because of the Obama administration’s renewed desire to negotiate.[27]

Strategically placed, NIAC helped bring Iran and the Obama administration together in negotiating a nuclear agreement between Iran and Germany and the five permanent UNSC members. The Obama administration adopted several NIAC positions in negotiating what would later become the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA, or Iran deal). It even named former NIAC employee Sahar Nowrouzzadeh as National Security Director for Iran, a post she occupied between 2014 and 2016.[28] NIAC, however, failed in its attempt not to constrain Iran to “breakout” phases by which it would have to abide to guarantee it would not develop an atomic weapon.[29] In Vienna and Geneva, where the negotiations took place, Parsi constantly appeared with the Iranian delegation. He also discussed business opportunities in Iran with Bijan Khajehpour.[30] That same year, NIAC created NIAC Action, a 501(c)(4) organization that would allow it to engage in lobbying.[31] After the Trump administration exited the JCPOA in 2018, NIAC has pushed for another understanding with Iran at the cost of American concessions.

NIAC’s mission is, according to its website, to empower Iranian Americans so that they can “advance peace & [sic] diplomacy, secure equitable immigration policies, and protect the civil rights of all Americans.”[32] For NIAC, the everyday concerns of Iranian Americans are merely a way of giving the Iranian regime more breathing space. Despite NIAC’s founding by Trita Parsi, Jamal Abdi is its current president.[33] As the information on NIAC’s website describes Abdi’s home state as Washington, where he studied at the state university (the University of Washington) from 2002 to 2006, Abdi’s birth most probably occurred within the United States.[34] After graduating, Abdi worked as a Policy Advisor for the House of Representatives between March 2007 and November 2009. According to NIAC’s website and LinkedIn, Abdi entered NIAC in November 2009 as a Policy Director, became NIAC Action’s Executive Director since its founding in July 2015, and took over the position of President of NIAC in August 2018, the same year that the Trump administration exited the JCPOA and one year before Trita Parsi founded the Quincy Institute.[35] Because of his background, Abdi helps lend credence to NIAC’s claims that the organization represents the concerns of ordinary Iranian Americans who want to promote normalized relations between Iran and the United States.

Most of NIAC’s staff is Iranian American in origin and politically leftist. Among the staff’s other Iranian Americans, one is Kurdish (Operations Manager Sara Hawrami) and another is Jewish (Community and Advocacy Associate Etan Mabourakh).[36] Hawrami, a Tennessee native, joined NIAC in 2021.[37] She lists no other activity between her graduation from college in 2019 and the start of her work at NIAC.[38] Meanwhile, Mabourakh, who hails from Florida, worked with Hakeem Jeffries in the summer of 2022 and for New York State Senator Zellnor Myrie between February and May 2020.[39]

Both Hawrami and Mabourakh have published retweeted aggressive comments against Joe Biden, Donald Trump, and Benjamin Netanyahu. In one of her retweets, Hawrami conveyed the idea that any thought of restoring the Iranian monarchy is tantamount to racism.[40] At the same time, Mabourakh insinuated that Senator John Fetterman wore a suit to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s speech to Congress because Netanyahu was Fetterman’s actual boss.[41] He also retweeted in support of Jamaal Bowman during this year’s Democratic Party primary.[42] In one of his tweets, Mabourakh claimed credit for organizing a coalition of 30 different organizations to promote treating advocacy campaigns favoring the democratic state of Israel as an influence campaign from Israel’s Ministry of Diaspora Affairs in the mold of those that autocratic Russia and Iran have waged.[43] Besides NIAC and the Iran enabler network’s Quincy Institute, many of the organizations that Mabourakh assembled, including American Muslims for Palestine, US Campaign for Palestinian Rights Action, and the MPower Change Action Fund, have links to Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood and coordinate the actions of Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP), which has terrorized Jewish students across American college campuses.[44]

Nevertheless, the presence of non-Iranian Americans inside NIAC is indicative of the importance that the organization assigns to normalized relations with Iran despite the supposed chief goal of looking after the concerns of Iranian Americans. In NIAC’s board, which surprisingly has a small number of two members, only one, OB/GYN Payman Jarrahy, is Iranian American.[45] Siobhan Coley, NIAC’s Board Chair, does not have Iranian origins.[46] Furthermore, NIAC’s Policy Director is Ryan Costello. Costello had served as a Program Associate at the Connect U.S. Fund—where he focused on nuclear terrorism through the Fissile Materials Working Group—before joining NIAC in 2013.[47]

NIAC’s 2021 990 Tax Form included around $1.2 million in grants from “10,000 individual donors.”[48] The only donors to which NIAC directly refers by their name are the Rockefeller Brothers Fund and the Ploughshares Fund (Ploughshares).[49] Ploughshares, in operation since 1981, is “singularly focused on reducing the threat of nuclear weapons” by pursuing targeted investments.[50] Those targeted investments seek “to create a global norm against nuclear weapons and increase the momentum toward zero,” focusing on Russia and the United States to reduce nuclear arsenals, prevent the emergence of new nuclear states, and look to understand the causes of nuclear policy in South Asian countries. Ploughshares’ tactics include traditional grants for long-term change, venture capital projects to allow new ideas to take root, and philanthropic campaigns to modify stakeholder behavior.[51] Ploughshares list non-proliferation efforts between the United States and the Soviet Union, winning the fight against “bunker buster” weapons, the 2010 New Start Treaty, the 1996 Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, and the JCPOA among its achievements.[52]

Ben Rhodes, one of President Barack Obama’s speechwriters, leader of the secret negotiations that reestablished diplomatic relations between the United States and Cuba, and advisor on the JCPOA, is one of Ploughshares’ board members. Other Ploughshares members include William Cohen, President Bill Clinton’s Secretary of Defense.[53] Within the Iran enabler network, the Quincy Institute, Alireza Vaezzadeh (Ali Vaez), and the International Crisis Group have been among Ploughshares’ other grantees. So have left-wing groups like J Street, MoveOn.org, and the National Committee on North Korea.[54] Ploughshares has not been exempt from anti-Semitism controversies. In 2017, employee Valerie Plame retweeted an alt-right article tying American Jews to wars fought by the United States.[55]

Another instance of the significance that normalized relations between the United States and Iran have for NIAC is that it promotes an initiative named Gender Champions in Nuclear Policy (GCNP) to foster the presence of women in nuclear negotiations.[56] The initiative also helps to refute the conception that NIAC is a regime acolyte since Iran is a regime that has repeatedly oppressed women. An instance of this is how the Iranian morality police beat Mahsa Amini to death for presumably wearing her hijab inappropriately.[57] Additionally, NIAC has focused on LGBT issues despite the fact that homosexuality is illegal in Iran.[58] Finally, NIAC has also publicly advocated for left-wing Iranian activists.[59]

The actions that NIAC considers its most important achievements starkly relate to sanctions and nuclear negotiations. The first category NIAC lists is “advancing peace & [sic] diplomacy.” The items in that category are helping pass the JCPOA, fighting sanctions legislations, avoiding a 2007 House of Representatives resolution in favor of a naval blockade of Iran, and securing commitments on favoring diplomacy over regime change during the 2020 election campaign.[60] The second category was “equitable immigration.” For this category’s achievements, NIAC listed securing multiple-entry visas for Iranian students, guaranteeing Iranian dual nationals were eligible for the Visa Waiver Program when applicable, ending the Trump 2017 travel ban, and upholding the green card process for Iranian nationals.[61]

Domestically, NIAC has pushed for companies like Apple to hire more Iranian Americans when they previously did not hire some individuals because of sanctions concerns, reversed a long-standing USPS policy of not sending mail to Iran in 2018, has lobbied for banks to exercise less scrutiny over the bank accounts that some Iranian Americans own—which had led to Bank of America shutting down 15,000 accounts owned by Iranian Americans—, has endorsed political candidates like former Washington Lieutenant Governor Cyrus Habib and helped defeat hardliners on Iran such as Congressman Dana Rohrbacher in 2018.[62] In what concerns sanctions, NIAC has only supported targeted sanctions on Iran, requested their withdrawal from communications equipment, and secured a permanent exemption for humanitarian organizations in 2013. NIAC even successfully pushed for the National Geographic Society to change the name of the body of water overlooking the Iranian coastline in its maps. That name, previously Arabian Gulf, became the Persian Gulf.[63] Recently, NIAC ensured a 2021 commitment from the Biden administration to end the Trump travel ban, finally opened NIAC Academies in 2022 to train Iranian American leaders—23 years after the 1999 Trita Parsi proposal—, blocked Texas Senate Bill 147, which restricted land purchases by citizens of countries openly hostile to American interests in 2023 and made the Census Bureau include Iranian Americans as a subcategory of the Middle East and North African (MENA) primary racial category. NIAC has also sought to prevent an Iran travel ban.[64]

NIAC has repeatedly opposed Israeli interests. After the October 7 attacks in 2023, NIAC did acknowledge some Hamas atrocities and lamented the Hezbollah attack on children playing soccer on a playground in the Druze village of Majdal Shams in July 2024.[65] NIAC has supported a ceasefire in Gaza, whose result would be Hamas continuing to exist.[66] Despite continued Iranian and Hezbollah attacks on Israeli civilians, NIAC has demanded that the United States not allow the Middle Eastern conflict to escalate.[67] It has also established a moral equivalency between Israel and Hamas.[68] Because it dislikes Israeli policies, NIAC has opposed military aid to Israel, called for a boycott of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s speech to Congress, and, after the Israeli strike that killed Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh, lamented dashed hopes for a quick ceasefire and stated that, after having exercised restraint, Iran, needed to retaliate to save face.[69] As this declaration shows, NIAC shies away from condemning the Iran regime. In January 2024, after an Iran-affiliated militia killed 3 US service members, NIAC only expressed a concern about regional escalation.[70]

Given its positions on Middle Eastern affairs, and as the case of Hassan Daioleslam shows, NIAC has been swift in countering its association with Tehran’s geopolitical interests. The first frequently asked question that NIAC cites on its website is whether it lobbies for Iran, which NIAC denies for obvious reasons.[71] NIAC does acknowledge NED grants during its early years and also mentions donations from Norway’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs between 2010 and 2012 that totaled around $170,000 but cites that two-thirds of its funds come from small donors and mentions its Platinum Seal of Transparency, awarded by Goldstar. For NIAC, the people who oppose them promote “misinformation” and represent “many in the pro-intervention political sphere, others in the rightwing pro-Israel crowd,” and some “Iranian dissident groups in the diaspora.”[72]

Regarding the Iranian diaspora, NIAC has attempted to weaken the claims and voices of the vast majority of Iranian Americans, who are opposed to the Islamic Republic regime. To do this, NIAC has sought to cast individuals in the Iranian American diaspora that favor regime change, and vocally oppose their policies as irrationally angry and opposed to constructive dialogue and to giving peace a chance because of their traumas. To that end, NIAC has received assistance from journalists who were sympathetic toward the JCPOA and normalization efforts and, to score points with Iranian allies, it has also looked to characterize a large percentage of American Jews and dissident-led diasporas, such as the Cuban and Venezuelan diasporas in the United States, as dangerously unhinged.[73]

In a Politico article, journalist Daniel Block defended Sherry Hakimi, who had supported the 2015 Iran deal and had met in person with Mohammad Javad Zarif after people in the diaspora attacked her, even to the point of sending death and rape threats.[74] Hakimi had participated in the NIAC-promoted Camp Ayandeh—which focused on Iranian American heritage—in 2008 as part of the Iranian Alliances Across Borders (IAAB).[75] He also defended Sanam Naraghi-Anderlini, who, in November 2016, had been a panelist at a NIAC event regarding what to expect regarding American Iran policy during the Trump administration.[76] Block also quoted Ali Vaez, who accused sectors in the Iranian American community of trying to “intimidate and silence people.”[77] In that same article, Block considered the case for normalization with Iran “compelling” and regarded Iranian Canadian dissident Kaveh Shahrooz as a “bombastic voice” that did not provide sufficient evidence for his claims, whose receipt of threats was a mere assertion, and whose discomfort at receiving those threats was ironic given Shahrooz’s frequent use of strong language.[78]

NIAC has expressed that, despite its (nominal) “opposition” to the Iranian regime, its constitutionally protected right to free speech entitles it to claim different views. Legally, this may be true. However, by doing so, NIAC has helped the Iranian diaspora remain divided—as it has been since 1979 when it used to come together under the Confederation of Iranian Students (CIS)—and thereby benefit the regime.[79] The Iranian diaspora expresses itself on news outlets with divergent views, such as BBC Persian, Manoto, Radio Farda, IranWire, and Iran International.[80] The Iranian opposition is split between far-right, liberal, leftist, social democratic, and monarchist factions. In February 2023, after the Woman, Life, Freedom Movement gained strength after the killing of Mahsa Amini the previous year, a conference at Georgetown University that included renowned diaspora personalities like former Iranian crown prince Reza Pahlavi, journalist Masin Alinejad, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Shirin Ebadi. Even though the meeting led to the Mahsa Charter and the establishment of the Alliance for Democracy and Freedom in Iran (AFDI) by March, the meeting had already lost two prominent members. This infighting continued until most of the alliance disintegrated by April 2023.[81] Despite NIAC not being the chief factor impeding the opposition from coming together, it certainly helps the Iranian diaspora stay disorganized and thereby helps the regime stand strong.

One important common denominator in NIAC’s preferred policies is that, in the name of furthering exchanges with people in Iran and creating mutual understanding, Iranian university students stand to benefit the most. With multiple entry visas, Iranian students can now visit Iran more often. With the changes in the university admissions policies that NIAC has promoted, more Iranians with active links to their homeland will access cutting-edge research. NIAC’s initiatives help Iran-based students access the American financial system when they otherwise would not. Fighting the Trump administration’s travel ban means that Iranians with links to the Islamic Republic, including some of the students’ family members, are entering the United States at higher rates. Lenient vetting of Iranian students in the United States presents many worrying outcomes that are not mere suppositions.

In countries where Iranian students have been more active, the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) demands cooperation from every Iran-based student and academic in serving the Islamic Republic. In Sweden, the IRGC uses student exchange programs to seize research such as “drone technology, artificial intelligence, data management and software for the military industry,” as Alireza Akhondi says.[82] In a similar case, Iran has gained knowledge from Cambridge University to make the kamikaze drones it has handed Russia to support its invasion of Ukraine because of a British-Iranian research program.[83] Iran has also obtained European components to manufacture its drones.[84] Because some Iranian students have benefited the regime militarily, it is less surprising that some of these students also advance the Islamic Republic’s political objectives. Since many prominent personages in the Iran enabler network initially came to the United States as students and the number of Iranian students in the United States has more than doubled to more than 10,000 since 2010, NIAC’s work in enlarging the network’s reach is paramount.[85] After examining the diaspora pillar, the paper shall review the network’s ideological pillar.

The Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft (Quincy)

Founded in 2019 with a Koch Foundation and Open Society Foundations grant, the Quincy Institute is a think tank that looks to “rethink[] U.S. foreign policy assumptions” given a multipolar world and overcome the limitations of the military-industrial complex when doing so.[86] For Quincy, locally solving local problems, American restraint, involving itself in debates, and promoting journalism through the Responsible Statecraft magazine are the methods Quincy uses to accomplish its objectives.[87] The motives that Quincy brandishes to justify its approach are looking after the interest of the broader public, respecting international law and shunning worldwide supremacy, using war as a last resort, and bolstering the authority of Congress. For this reason, Quincy enjoys the backing of non-interventionists on both sides of the political spectrum and attempts to work to bridge the perceived foreign policy gap between what think tanks and academia propose.[88]

According to a tax filing at the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), former Army Colonel and historian Andrew Bacevich and NIAC’s Trita Parsi are Quincy’s co-founders.[89] According to journalist Armin Rosen, Parsi’s $275,000 salary as Executive Vice President at the time, more than five times Bacevich’s stipend of $50,000, was a sign that Parsi ran and still manages Quincy.[90] This event is not surprising. For Parsi, who is bent on normalizing Iran’s heavily ideological and anti-American Islamic Republic on the world stage, Quincy is a step up from NIAC because it allows him to favor Iran and its allies on multiple fronts. Quincy also offers Parsi a platform from which he could gradually turn normalizing relations with Iran into a bipartisan issue.

A reading of Quincy’s proposals shows that non-intervention for its sake—even when being more active internationally would prove the most effective course of action—and downright but subtle hostility to Israel are at the core of its proposals. Repeatedly, Quincy has urged Israel to exercise restraint to prevent regional tensions from escalating.[91] Rather than celebrating the benefits of the Abraham Accords in which Israel normalized relations with four Arab states (the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Sudan, and Morocco), Quincy acknowledged some of their benefits.[92] Nevertheless, it expressed ample reservations because the Abraham Accords rendered Iran queasy and because they made a détente between Saudi Arabia and Iran more unlikely, even though more widespread recognition of Israel can reduce tensions and American involvement in the unstable Middle Eastern theater: one of Quincy’s goals.[93]

Regarding its policy of non-intervention for its own sake, Quincy does fulfill its ambition of turning every American foreign policy assumption on its head through its recommendations. Anatol Lieven, Director of the Eurasia Program at Quincy, has suggested that Russian peace terms are relatively peaceful and realistic and that Ukraine should accept them to prevent more losses despite the precedent that it could set and the possible weakening of American relations with NATO allies Poland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.[94] He also considered a June 2024 Geneva summit a way to advance that initiative in the long run.[95] Lieven has also expressed that the United Kingdom’s foreign policy should be increasingly independent of the United States, fundamentally transforming the special relationship between the Americans and the British.[96]

Quincy has proposed that the United States negotiate another nuclear deal with newly inaugurated President of Iran Masoud Pezeshkian even though Iran has destabilized the Middle East by sponsoring Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Houthis.[97] Concerning Cuba, which has recently propped up Nicolás Maduro’s dictatorship in Venezuela, Quincy has openly suggested disregarding the concerns of Cuban Americans in favor of the larger picture.[98] Quincy has also indicated that Congressmen like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Greg Casar showed the rest of the United States how to deal with the new leftist leadership in Latin American countries such as Brazil, Chile, and Colombia.[99] Concerning Brazil in particular, Quincy has proposed that differences over Ukraine were not vital enough to affect American bilateral ties with Brazil in any shape or form.[100] Regarding China, Quincy has advocated for giving the government more weight in international mediation; Quincy has also shown “pragmatism toward the persecution of Uyghurs” and proposed negotiating maritime agreements that would limit the extent of freedom of navigation operations in the South China Sea.[101] In the Korean peninsula, Quincy has advanced the idea of not confronting North Korea whenever its regime makes overtures toward dialogue, even though these supposed advances have been spurious in the past.[102] In Syria, Quincy has considered “the survival of the Assad regime” the best among the worst alternatives and has suggested the withdrawal of American troops from that country and Iraq.[103] This last action would only solidify Iran’s position by letting it reach the Mediterranean Sea completely untrammeled.

In Afghanistan, before August 2021, Quincy suggested an American withdrawal without any preconditions.[104] Implementing this strategy had pernicious consequences for America’s national interests since it entailed that the Taliban would resume their rule at Afghanistan’s helm, that 13 United States service members would die in Kabul Airport during the evacuation, and that a significant migration and humanitarian crisis took place.[105] In Yemen, Quincy has advocated for an end to foreign intervention with the pretext of safeguarding Yemeni sovereignty.[106] According to Quincy’s non-resident fellow Shireen Al-Adeimi, the attacks by Shiite Houthi militias on international shipping passing through the Red Sea and the Bab al-Mandeb Strait were an attempt at “genocide prevention” in Gaza.[107] In the Sahel region, which has recently seen a rise in jihadist movements, a rejection of French influence, and Russian inroads in countries like Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Guinea, Quincy’s recommendation was to scale down French and American operations, without concern about Russia or China pushing the region’s states toward their sphere of influence.[108] Quincy has also recommended a change in policy about Belarus, despite its increasing alignment with Russia.[109]

Although Quincy looks to bolster the powers of Congress, it is not receptive to state governors and legislators when they intend to shape foreign policy. In Quincy’s Responsible Statecraft magazine, Junior Research Fellow Nick Cleveland-Stout wrote in rejection of state bills mandating the registration of workers of foreign-owned companies as foreign agents. He also expressed reservations about naming “countries of concern” such as “China, Russia, Iran, North Korea, Cuba, Syria, and Venezuela.” His argument in favor of international issues requiring review by the federal government notwithstanding, the article’s title of letting “the feds handle foreign influence” indicates hostility to the states exercising their constitutional powers as an equal level of government in a federal republic.[110]

By itself, it is not questionable to consider that the best way to serve American interests is by reducing the involvement of the United States around the globe and giving way to a world order less based on unilateral action and focused on upholding a set of international rules. Moreover, many people in the Quincy Institute may pursue this policy with the best intentions. Nevertheless, simultaneously implementing every Quincy policy would inevitably lead to a power vacuum. This power vacuum would have dual effects. The first would be that, despite reduced American coercion, many governments would not have the financial and knowledge resources to step up if the United States left. The second one would be that adversaries of the United States, unwilling to be rule-takers any longer, such as Russia and China, would aggressively irreversibly erode or replace American influence worldwide. This outcome would humiliate the United States’ international standing and make it harder for Americans to influence their access to foreign markets and overall prosperity. In short, Quincy’s recommendations are utterly reckless. Given Trita Parsi’s Iranian links and executive role at the Quincy Institute, it is not outlandish to conclude that the basis for the organization’s proposals is a deliberate scheme to undercut and stultify the United States to benefit the Iranian regime and its international allies.

Complicit with Quincy in this initiative of American decline by design is an intricate donor network. The donors that Quincy lists include the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Colombe Foundation, the East-West Bank Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Nasiri Foundation, the Open Society Foundations, the Pivotal Foundation, Ploughshares, the Samuel Rubin Foundation, the Stand Together Trust, the Stichting Giustra International Foundation, the Arca Foundation, and the Streisand Foundation.[111] Quincy’s expanded donor list for the last twelve months also includes the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, the Robert Bosch Stiftung, and many of its board members.[112] The Koch Foundation—which had handed Quincy part of its initial assets—no longer figures among Quincy’s funders after 2021, meaning that Quincy is acquiring an increasingly left-wing bent.[113] According to that webpage, Lawyers for Reporters also gives Quincy non-financial support by helping it with litigation challenges.[114] The Cyrus R. Vance Center for International Justice (Vance Center) started Lawyers for Reporters.[115] The Vance Center also funds Fundación Pro Bono in Chile, which in 2019 sympathized with the goals a series of protests that ended in riots that ravaged capital city Santiago, destroyed large swaths of the local subway system, and led to the country paralyzing itself by participating in two failed constitutional revision processes.[116]

For 2022, Quincy’s revenue amounted to $4,857,094, roughly $1.1 million less than in 2021, according to its 990 Tax Form. However, what is remarkable is that Quincy experienced a growth in salary expenses from around $3 million to $3.7 million, which probably points to higher hiring numbers. By working at Quincy rather than at NIAC, Parsi has been able to quadruple, at least, the total resources that he can manage and maintain the same compensation levels he previously enjoyed at NIAC (between $270,000 and $290,000).[117] Quincy’s resources have allowed the organization to continue operating normally despite a negative revenue of $128,775 in 2022. In terms of programs, Quincy spent $4,160,186 in 2022. The chief program expenses were the General Program ($880,326), the Middle East Program ($825,685), and the Communications Program ($655,473).[118] The prominence of the Quincy Institute Middle East Program, just like its proposals, is another way of lending credence to the conception that the think tank functions to allow Trita Parsi to spread his ideas of rapprochement with Iran on a grander stage.

Although he is Quincy’s cofounder, Trita Parsi only holds the position of Executive Vice President.[119] Lora Lumpe, who formerly worked for the George Soros-funded Open Society Foundations as Advocacy Director, currently holds the position of CEO of the Quincy Institute. According to Quincy’s webpage, Lumpe “engaged in strategic grantmaking, field building, and campaigning aimed at ending America’s endless wars” during her time at the Open Society Foundations.[120] According to Influence Watch, Lumpe has also participated in “[the] Federation of American Scientists, the Friends Committee on National Legislation, the Small Arms Survey, the United Nations, and American Friends Service Committee.”[121] Lumpe’s hiring is one proof that Trita Parsi—and not she—controls Quincy, despite her CEO role. Although Quincy’s founding occurred in December 2019, Lumpe’s selection as CEO took place three months later, in March 2020.[122] At the time, Trita Parsi personally commended Lumpe for her hiring.[123] After Lumpe’s hiring, Parsi suffered no demotion. The Quincy report that named Lumpe CEO also described Parsi as Quincy’s Executive Vice President.[124] Consequently, one can deduce that Parsi helped select Lumpe despite his lower nominal rank at Quincy and his non-participation in Quincy’s Board. This also leads to the possibility that, because of his previous work for NIAC, Parsi intended to give Quincy a more independent image by showing some distance from top management.

A look into Quincy’s board and staff provides a comprehensive picture of the organization and its people, some of which express problematic views. Some Quincy staff have contributed to make life difficult for Jewish students on college campuses. For instance, Quincy Advocacy Associate Rawan Abhari, who worked for Congressman Andy Kim, accused Israel of apartheid and defended Florida State University (FSU) student and SJP member Ahmad Daraldik, after he managed to wrestle the position of FSU Student Senate President from someone else, for statements comparing Israel to Nazi Germany, for comments accusing Zionists—the overwhelming majority of whom are Jews—of not empathizing with the Black community because of their supposed white skin color, and for directly accusing Jews of “mak[ing] everything about themselves.”[125] Abhari has also promoted the boycott, divestment, and sanctions (BDS) movement.[126]

Other Quincy staff have direct link to Islamist organizations or countries. Senior Video Producer Khody Akhavi has worked for Al Jazeera English, which receives most of its funding from Muslim Brotherhood-friendly Qatar.[127] Director of Advocacy Tori Bateman has worked for the American Friends Service Committee (ASFC), with direct links to the US Campaign for Palestinian Rights (USCPR).[128] Senior Advisor Eli Clifton has directly accused television network Fox News and right-wing think tanks like the Middle East Forum of fanning Islamophobic sentiments.[129] Amir Handjani, a Quincy Non-Resident Fellow, is even part of the board of RAK Petroleum, based in the Emirate of Ras Al-Khaimah, in the UAE.[130] Even though the UAE is not an Islamist country like Qatar, simultaneous participation in a foreign policy think tank and a foreign oil company may signal a potential conflict of interest. Moreover, Ras Al-Khaimah is an Iranian money laundering hub.[131] Another one of Handjani’s conflicts of interests is his involvement in PG International Commodity Trading Services, which represents American agricultural company Cargill in Iran. Cargill still operates in Iran because United States sanctions there do not cover agriculture.[132] Another one of Handjani’s previous conflicts of interests is that, as part of the Atlantic Council’s board, he donated $500,000 to that think tank, some of which he earmarked to the Future of Iran Initiative.[133]

Reporter Connor Echols, who worked for Quincy until June 2024, holds two types of links to Qatar. The first is his work for the Arab Center Washington DC, whose primary affiliation lies with the Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies (ACRPS).[134] ACPRS also has sister organizations in Paris and in two Muslim-majority countries with strong Islamist and previous Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) presence before the Oslo Accords: Lebanon and Tunisia.[135] The second link relates to Echols’ journalism degree from Northwestern University because Northwestern has a Doha campus whose degree offer revolves almost entirely around journalism.[136]

Eurasia Program Director Anatol Lieven has previously taught at Georgetown University in Qatar, where the Qatar Foundation has access to the intellectual property of research conducted therein and significant sway over the curriculum.[137] Deputy Director of the Middle East Program Adam Weinstein has worked for NIAC and “regularly travels throughout Pakistan.”[138] Non-Resident Fellow Shireen Al-Adeimi has repeatedly sought to counter Saudi Arabia and the UAE’s involvement in the Yemeni Civil War.[139] Quincy’s Iran Program director is William H. Luers, Non-Resident Fellow and former US Ambassador to “Czechoslovakia (1983-1986) and Venezuela (1978-1982)” and “Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Europe (1977-1978) and for Inter-American Affairs (1975-1977)” inside the State Department.[140]

Many other Quincy staff hold positions that imperil the continued existence of American ally Israel. Director of Communications Jessica Rosenblum has previously worked for J Street—a fringe voice within the American Jewish community that looks to revisit United States policy toward Israel—as Senior Vice President of Jewish Engagement.[141] Research Fellow Annelle Sheline resigned her position at the Department of State’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor’s Office of Near Eastern Affairs in protest of President Biden’s support of Israel during its defensive war against Hamas.[142] Sheline is also Non-Resident Fellow of the Baker Institute, which has promoted Mexican president-elect Claudia Sheinbaum—often at odds with American foreign policy interests—and doubted the effectiveness of Texas’ border security strategy to counter illegal immigration.[143] Non-Resident Fellow Nando Villa also heads Hollywood studio Exile Content, focused on Latino audiences, which is strange for someone working at a think tank like Quincy. In 2016, Villa’s documentary The Naked Truth: Trumpland received an Emmy Award nomination.[144]

Unlike NIAC, Quincy’s board is entangled with part of the upper crust of American society. The Chairman of the Board of the Quincy Institute is Stephen Heintz, President of the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, which supports leftist causes and has “an endowment of approximately $1.2 billion.”[145] Board Member Lea Hunt-Hendrix, a Hunt family heiress, is co-founder and former Executive Director of Solidaire, which seeks to “support resistance” to “dismantling and disrupting extractive, exploitative, and oppressive systems steeped in structural racism,” aims to “fund imagination and futures” by “envisioning and creating (…) decolonized systems that recognize and respect the dignity of all oppressed peoples,” and aims to upend American institutions through “[l]iberat[ing] wealth to support Black liberation and Indigenous Sovereignty.”[146] Among the organizations Solidaire supports is Palestine Legal, which assists pro-Palestinian protesters who get into trouble with law enforcement.[147] Hunt-Hendrix also works as “a Senior Advisor at the American Economic Liberties Project and a member of the Board of Directors of the Solutions Project.” Currently, one of the American Economic Liberties Project’s board members is Laleh Ispahani, who heads Open Society’s American operations.[148] Staff member Faiz Shakir has previously advised Bernie Sanders.[149] Personally, Hunt-Hendrix participated in the Occupy Wall Street Movement in the early 2010s and, after 2017, founded progressive political organization Way to Win to mobilize voters in its stated goal to build a multiracial democracy.[150] In 2020, Way to Win deployed $110 million in funding.[151] After Way to Win, Hunt-Hendrix also helped establish what is today the Valiente Fund to help make Latino Americans a more cohesive voter bloc.[152]

Board Member Jessica Matthews headed the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace between 1997 and 2015 and has also held positions in the Council for Foreign Relations, the Brookings Institution, the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, and the editorial board of The Washington Post, among others.[153] Another board member at Quincy is Iranian American Francis Najafi, who is active in the Chief Executives Organization, the World Presidents’ Organization, and the Aspen Institute think tank.[154] Besides those commitments, he is the founder and CEO of the Pivotal Group. The Pivotal Group is a private equity firm that has included some Ritz Carlton and St. Regis hotels in its real estate portfolio.[155] Board Member Thomas R. Pickering is a former ambassador and was US Representative to the United Nations under George H.W. Bush. During the Clinton administration, he was Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs.[156] In 1988, Pickering denounced Israeli expulsion of terrorists against the backdrop of the First Intifada.[157] Board Member Liz Theoharis is Co-Chair of the Poor People’s Campaign.[158]

Board Member Katrina vanden Heuvel is Editorial Director and Publisher of The Nation and directs the American Committee for US-Russian Accord (ACURA).[159] ACURA has dismissed warnings about Vladimir Putin’s expansionist ideology in Russia and has decried the Washington, DC meeting for the 75th anniversary of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) for being a presumed self-congratulatory event.[160] Vanden Heuvel is also part of the Council of Foreign Relations and supported Senator Bernie Sanders in his 2016 presidential bid.[161] Board Member Stephen Walt is a contributing editor at Foreign Policy. He notoriously criticized domestic American support for Israel in the book The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy, which he co-authored with University of Chicago professor Dr. John Mearsheimer.[162] Another one of Quincy’s board members is venture capitalist Michael Zak, who founded Cornell University’s China & Asia-Pacific Studies program, heads Boston’s flagship National Public Radio (NPR) station, and also partakes in the Board of the Center for a New American Security (CNAS).[163]

Trita Parsi and His Motives

Despite Trita Parsi’s prominent role within the Iran enabler network, this paper has avoided dealing with him in depth up to this point. There is a reason behind this approach. Although NIAC and Quincy are deeply intertwined with Parsi since he contributed to their founding, they are separate organizations. Hence, it is better to draw the first contours of the Iranian enabler network to comprehend better how details in Parsi’s background and ideology influence the network’s functioning and can also direct the actions of other members.

Trita Parsi was born in Ahvaz, in the Iranian province of Khuzestan.[164] His family was Zoroastrian.[165] His father, Touraj Parsi, was a college professor whom Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini had arrested. Just after the Iranian Revolution succeeded, Trita Parsi emigrated to Sweden with his family when he was four.[166] The timeline of Touraj Parsi’s arrests, both before and after the Iranian Revolution, and the destination that the family chose after fleeing Iran indicate that Touraj Parsi had left-wing sympathies. Heshmat Alavi reports that Touraj Parsi belonged to the communist Tudeh Party.[167] This left-wing support is no surprise. For several decades, political parties of Islamist and leftist persuasion had allied themselves in opposition to the Shah. Ayatollah Abol-Ghasem Kashani had been an ally of Mohammad Mosaddegh during his 1951 nationalization of the Iranian petroleum industry. He also supported him as Speaker of the Majlis (the Iranian legislature). The 1953 coup that overthrew Mosaddegh did not occur until Kashani withdrew his support from the government.[168] In 1978 and 1979, left-wing and Islamist political forces coordinated and helped topple the Shah. Even today, despite its exclusion from Iran’s political life, the Freedom Movement of Iran—affiliated with Mosaddegh’s legacy—still declares its support for the Islamic Republic regime.[169] Conversely, the Islamic Republic joined the left-wing Non-Aligned Movement in 1979 to shore up its international legitimacy, still uses anti-imperialist and Third World rhetoric to this day, and cites the 1953 coup that overthrew Mosaddegh as a justification for its hostility to the United States.[170]

Trita Parsi’s time in Sweden may have also rendered him more supportive of Iranian interests. Moreover, Trita Parsi spent many years of his childhood under the effects of Olof Palme’s premiership (1969-1976, 1982-1986). In foreign policy, Palme led Sweden in a decidedly leftist direction that glanced warmly at any movement with whichever tinge of Third World liberation as an ideology. For instance, although Palme heavily opposed Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship in Chile, he was receptive to Fidel Castro in Cuba and even visited him. In Central America, Palme supported left-wing Guatemalan guerrillas and the FMLN movement in El Salvador. On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, Palme supported and funded organizations like the Polisario Front in Western Sahara against Spain and Morocco, the PLO, and the African National Congress (ANC) in South Africa—at a time when it was employing violent methods. In the Iran-Iraq War, Palme even served as a mediator.[171] Unlike the United States, which suffered from the trauma of the 1979-1980 embassy attack and hostage-taking, Sweden never broke diplomatic relations with Iran.[172] Just like NIAC and Quincy do, Palme considered Iran a normal country. Moreover, Trita Parsi’s archeologist father Touraj never stopped being involved with Iran. At least during the 2000s, he was part of the Pasargad Heritage Foundation.[173] For these reasons, Trita Parsi’s leftist family and his upbringing in Sweden left an indelible mark on his ideological convictions and more sympathetic to the Iranian government, as opposed to most diaspora Iranians.

The 1990s were some of Trita Parsi’s defining years. Starting in 1994, Parsi studied for bachelor’s and master’s degrees in Political Science and Government at the University of Uppsala, one of the finest in Sweden. According to his LinkedIn profile, Parsi finished his master’s degree in 2000. During those years, Parsi also studied for a master’s degree in International Economics at the Stockholm School of Economics between 1996 and 2000. He studied Political Science and Government at the University of Stockholm between 1995 and 1996.[174]

During that time, not only did Parsi create IIC; he also established his reputation as an unapologetic Iranian nationalist. Journalist Armin Rosen liked Parsi to two Google posts, both under Parsi’s name, dating to 1996 and 1997—two years before Google released its search engine.[175] The 1996 post was an unabashed ode to Parsi’s country of birth, which declared that “[t]here is no substitut (sic) for Iran! There is a reason why all my letters end with ZENDE BAD IRAN [long live Iran].”[176] In that post, Parsi also declared some lines before that, he wanted to see a “free,” “proud,” and “strong” Iran. He also mentioned that the one-million dead in the Iran-Iraq War the previous decade “still died for Iran” and perished so “that another beautiful Iranian child could be born and be called Shirin or Darius.” He also mentioned phrases that were problematic for American national interests, including “[o]ur brothers and sisters did not die for us so we could marry an [A]merican and call our child Betty-Sue or Joey, they did not die so we could speak [E]nglish to our children. WE OWE IRAN OUR LIVES.”[177]

The 1997 post, directed at Kenneth R. Timmerman of the Foundation for Democracy in Iran, included vulgar and biased, if not anti-Semitic, language. He accused Timmerman of not caring about the lives of Iranians and thought that “[i]t is just unbelievable that an American thinks Iranians are so stupid that they would buy your crap.” Regarding Israeli opposition to Iranian policies, he said that “[b]y your name, I suspect that you are a Jew.” He also mentioned that, often, “Israelis run their business under the safety of an American flag.”[178] In that post, Parsi distinguished between reformist and radical factions in Iran’s regime and accused Timmerman of emboldening the radicals.[179] Given Parsi’s actions, it is plausible to believe that, despite his non-Islamist personal background, Parsi may be aligned with the Iranian regime because it represents the continuity of a Persian polity, just as Vladimir Putin showed nostalgia for the Soviet Union as a Russian polity in 2005 by considering the USSR’s collapse as a “geopolitical tragedy.”[180]

Between 1997 and 1998, Parsi had the opportunity to work for the Swedish delegation to the UNSC, when Sweden was a non-permanent member, which shows Parsi’s Third World and nationalist credentials.[181] During that period, as a fortunate coincidence, he specifically reviewed the dossiers of locations of interest to Iran: the Western Sahara, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan.[182] After the Revolution, Iran became friendlier to the left-wing Polisario Front than under the Shah. The Polisario Front is a Western Saharan guerrilla movement that looks to wrestle control of the region away from Morocco. Morocco even protested against Iran in 2018 for supposedly funneling money to the Polisario Front through Hezbollah.[183] In 1997 and 1998, Sweden, together with the rest of the international community, attempted to organize a self-determination referendum for the Western Sahara. In Afghanistan and Tajikistan, which have a rich historical Persian heritage and where the common language is still almost entirely based on Persian, Sweden looked to ensure that both countries’ civil wars ended peacefully and did not compromise the stability of surrounding states.[184] In the case of Tajikistan, Sweden helped achieve this by 1997.[185] In the UN General Assembly, Parsi also addressed “human rights in Iran, Afghanistan, Myanmar, and Iraq.”[186]

Another one of Parsi’s motives has been to acquire prestige steadily to spread his message. As he was establishing NIAC, Parsi enlisted the help of Rutgers professor Hooshang Amiramahdi to obtain a work visa around 2001 and to receive an introduction to then-Iranian diplomat Mohammad Javad Zarif.[187] According to The Washington Times, Amirhadi would later register as a candidate for Iran’s presidential election in 2005.[188] He has received participation bans from the Iranian regime ever since.[189] Parsi also worked for the Iranian company AB during some of those years.[190]

Between 2001 and 2006, Parsi completed a PhD at the School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) at Johns Hopkins University.[191] For his thesis, he chose Francis Fukuyama, who in 1992 famously predicted an end to history, as his advisor. He also chose former Carter administration National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski to be part of his dissertation committee.[192] Parsi would later turn his thesis into a book called Treacherous Alliance: The Secret Dealings of Israel, Iran, and the United States.[193] Published in 2007 and containing direct quotes from Iranian and Israeli public officials, Parsi’s work argues that there is a complex triangular relationship between Israel, Iran, and the United States, and—continuing his interest with Jewish American lobbying efforts—Parsi accuses AIPAC of sabotaging normalization efforts between the United States and Iran.[194] Ever since Parsi obtained his PhD, “[h]e has served as an adjunct professor of International Relations at Johns Hopkins University SAIS, New York University, Georgetown University, and George Washington University, as well as an adjunct scholar at the Middle East Institute, and as a Policy Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington DC.”[195]

As his work for Quincy and his thesis—with more liberal Fukuyama and more right-wing Brzezinski—show, Parsi has worked with people on both sides of the aisle despite his firm left-wing views. From 2001 to 2004, Parsi worked as a Foreign Policy Advisor to Republican Congressman Robert Ney of Ohio.[196] With links with Iran since the late 1970s and fluent in Persian, Ney was a perfect fit for Parsi’s views.[197] Ney is also proof of Parsi’s multi-pronged connections to the Iranian regime. In 2006, Ney resigned his seat before an imminent expulsion vote. He also pleaded guilty to a corruption investigation of Republican Party lobbyist Jack Abramoff. In 2007, he received 30 months in prison.[198] According to an article by Patrick O’Connor at Politico about the plea deal Ney’s chief of staff Will Heaton faced in 2007, Heaton admitted that “he and Ney both accepted ‘thousands of dollars (sic) worth of gambling chips’ during a trip to London from a foreign businessman who wanted to sell U.S.-made airplanes and parts to Iran.” This act was forbidden because Americans could not and still cannot help Iran obtain airplanes or airplane components.[199] The businessman involved in Will Heaton’s deal was Syrian national Fouad al-Zayat, who headed an aviation firm in Cyprus and was involved in aircraft transactions on behalf of the Iranian military.[200] In summary, as Trita Parsi’s connections demonstrate, he is a significant building block of the Iranian enabler network in the United States.

Rethinking Iran: The Network’s Secondary Protagonists

Within the Iranian enabler network, Trita Parsi and the Quincy Institute are the indisputable cornerstones of the ideological pillar. Nevertheless, they are not the only ones. Most of the network maintains academic connections to the two most prestigious universities of international relations in Washington, DC: Georgetown University and Johns Hopkins SAIS. Consequently, it is not surprising that the second organizational component of the network’s ideological pillar is the Rethinking Iran Initiative (Rethinking Iran) at Johns Hopkins SAIS. Professors Vali Nasr and Narges Bajoghli head the organization as co-directors. Currently, three SAIS students are on the staff of Rethinking Iran.[201]

Using language similar to that of NIAC and Quincy, Rethinking Iran considers that “the lens to understand Iran continues to be a very narrow one that does not consider the country’s complex realities.”[202] To counteract this perceived inaccuracy in depicting the landscape of the Islamic Republic, Rethinking Iran looks to supply the information it believes to be more precise. Those particulars include a noticeable left-wing bent and resemble the positions of NIAC and Quincy. For instance, Rethinking Iran categorizes the Israeli killing of Ismail Haniyeh as an attack against regional stability, lauds the China-sponsored deal between Saudi Arabia and Iran; and focuses on women, with a specific emphasis on the 2022 Woman, Life, Freedom Movement that resulted from the violent death of Mahsa Amini.[203] Not astonishingly, Rethinking Iran has generally rejected sanctions as a policy.[204]

In 2024, Nasr, Bajoghli, Virginia Tech academic Djavad Salehi-Isfanhani, and International Crisis Group (ICG) Iran Program Director Ali Vaez wrote a book named How Sanctions Work: Iran and the Impact of Economic Warfare. The work argues that rather than propitiating regime change and stymieing Iran’s nuclear program, sanctions embolden authoritarian regimes and only affect the population at large, thus disfavoring American interests.[205] The book asserts that sanctions create the ideal atmosphere for the IRGC to increase its smuggling and black market proceeds. It also mentions that, amidst its sanctions, Iran has reinforced its links with Russia and strengthened its domestic industrial capacity.[206] Although the book quotes some events that have materialized, its narrative is flawed.

History is the best proof of the effectiveness of sanctions. When the United States subscribed to the JCPOA in 2015, Iran gained the right to develop its nuclear program as long as it did not reach a breakout window in uranium enrichment. Even though it had to comply with International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) visits, it subsequently ignored them and constrained the entry of inspectors when it allowed them to come.[207] During that time, Iran increased its stranglehold over Iraq, bolstered Bashar al-Assad’s Syrian regime, and continued to support the Houthis in Yemen.[208] When the United States left the JCPOA in 2018 and reinstated some of the sanctions that it had stopped applying, the IRGC suffered considerable blows—as with the death of Qassem Soleimani in 2020—and an anti-Iranian axis consolidated, leading to the Abraham Accords, which shed some of the tension between Israel and the Arab states.

After the United States enforced sanctions less energetically since 2021, the anti-Iranian coalition has weakened, Israel has not normalized relations with any more Arab states, and, since October 7, 2023, it has waged war on seven fronts. Moreover, Iran has only grown closer to Russia because the latter country has faced increasing international isolation after it invaded Ukraine in February 2022.[209] Given the state of current affairs and the backgrounds of the book’s authors, it is easy to conclude that dispelling the effectiveness of sanctions is merely an attempt to justify normalizing American relations with Iran.

Narges Bajoghli is one instance of this case. Born in Iran, Bajoghli has barely shared personal information such as her hometown and the year of her move to the United States.[210] Bajoghli is a political scientist and anthropologist by training.[211] Between 2000 and 2004, she pursued a bachelor’s degree in Political Science at Wellesley College. Between 2002 and 2003, she took courses at the SOAS University of London (SOAS), known for its well-reputed African, Asian, and Middle Eastern programs. Between 2007 and 2009, Bajoghli pursued a Master of Arts in Anthropology at the University of Chicago. After that, she pursued a PhD in Anthropology at New York University, which she completed in 2016. That year, she worked at Brown University as a Postdoctoral Research Associate and became an Adjunct Professor at Johns Hopkins SAIS in 2018.[212] In 2019, Bajoghli published Iran Reframed: Anxieties of Power in the Islamic Republic, for which she interviewed young people joining regime-aligned paramilitary organizations such as the Basij, Ansar Hezbollah, and the IRGC. The book concluded that the regime had to tailor its message to a new generation and that class differences animated a large part of the lives of Iranian fighters.[213] The book could belong to a larger strategy of voiding the conception of the Islamic Republic as an ideological regime by determining that even the members of Iran’s most ideologically committed units have their standard of living as their primary motivation.

Another example is Vali Nasr. Born in 1960 to eclectic, current George Washington University Shia theologian Seyyed Hossein Nasr in Tehran, Nasr left the country for schooling in London in 1976. In 1979, with the advent of the Iranian Revolution, he moved to the United States to be closer to his father, who left Iran that same year.[214] Nasr then pursued bachelor’s and master’s degrees in International Relations at Tufts University, which Nasr concluded between 1983 and 1984, respectively. Between 1986 and 1991, he pursued a PhD in Political Science at MIT. After that milestone, Nasr held various academic positions at prestigious American universities, including Tufts University, Harvard University, and Stanford University. He also advised Richard Holbrooke at the State Department in Afghan and Pakistani affairs between 2009 and 2011. Between 2012 and 2019, he was the Dean of Johns Hopkins SAIS, where he still works as a professor.[215] Nasr has suggested subjecting Saudi-Israeli normalization efforts to the creation of a Palestinian Arab state, has expressed hopes about the new Iranian president, Masoud Pezeshkian, being a reformer in a regime where Ayatollah Ali Khamenei wields power, and has considered that dealing with Iran reinforces the Middle Eastern order and adds an element of stability.[216] As this section has shown, Rethinking Iran and its co-directors complement Trita Parsi’s contributions to the Iran enabler network’s ideological pillar and intersect with its bureaucratic pillar.

The International Crisis Group (ICG), the Iranian Experts Initiative, and Alireza Vaezzadeh